“I broke in and I planted an idea. [One] simple idea that I knew would change everything.”

Ever since redefining the realist capabilities of superhero films, Christopher Nolan has been negotiating the separation between mainstream audience accessibility and his own personal aesthetic. Pivoting from developing a Howard Hughes biopic – unfortunately coming hot off the heels of Martin Scorsese’s monumental “The Aviator” (Marty’s most underrated, in this writer’s mind) – the maestro of time and space re-envisioned Frank Miller’s “Batman: Year One” through the lens of a gritty street film junkie; beginning with heavy John Huston influence, following a weary but privileged American on an adventure to another land, and ending as a meeting point between a Sidney Lumet character piece and Michael Mann epic.

“The Dark Knight” could very well be described as “Heat” by way of “Serpico.” Despite its radical departure from typical genre trappings – particularly in regards to the tragic ending – Nolan found audience champions like never before. His next four films would net nearly $4 billion at the box office, yet, despite the near unanimous acclaim (pre-”The Dark Knight Rises” dividing audiences), the most successful filmmaker of the century still found himself without an Oscar nomination for Best Director under his belt (his most egregious snub was the same cursed year Tom Hooper stole David Fincher’s statue). Continuing this odd, almost godly cultural narrative, “Dunkirk” – effectively an experimental art film – finally found him Academy success. The film’s innovative montage is more Sergei Eisenstein or Abel Gance than it is a war film a la Steven Spielberg or Oliver Stone.

And so we come to the concept of a paradox, which has come to define Nolan’s career as an artist; a superhero savior who choses to be the city’s villain; a magician who obsesses over a single trick so much he turns it into science experiment; a dream thief who wants to live in the waking world because he turned his wife’s into a nightmare. Even through dialog, Nolan cannot escape his fixation on paradoxes and parallelisms; “Mankind was born on earth. It was never meant to die here.” With “Oppenheimer,” he’s engineered a historical parallax.

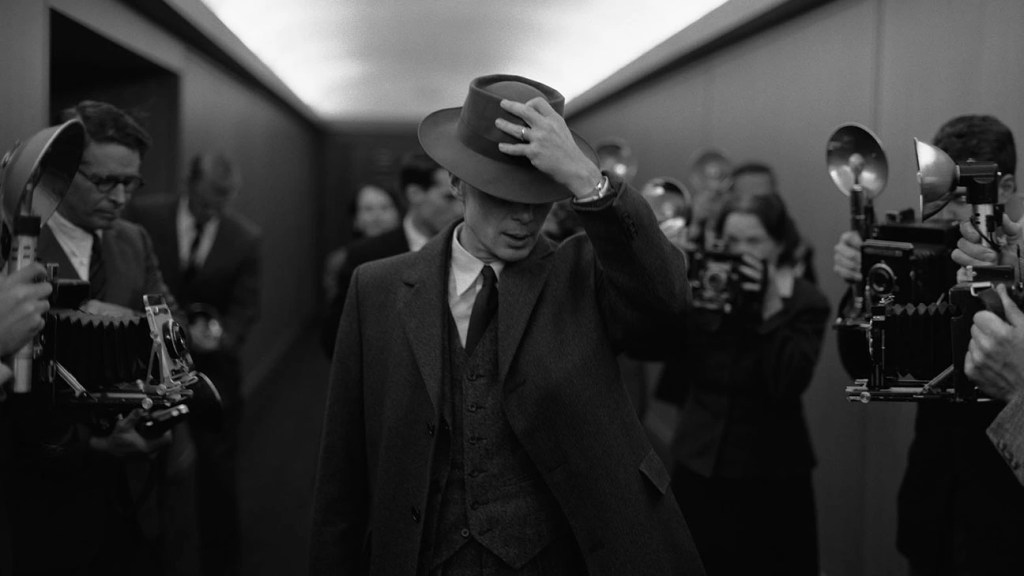

Shrewdly structured into two distinct parts and perspectives. “Fission,” shot in color, from the titular subject’s (Cillian Murphy) point of view, and “Fusion,” shot in tangible black and white, following the arms-race viewpoint of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), as he battles to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate as the next Secretary of Commerce. In anticipation of his always ambitious structuralism, Reddit made jokes about the film being a courtroom drama in reverse, and, while that’s a colossal over-simplification, it’s orbiting the conceit’s event horizon. It’s a deposition film by way of “JFK,” with some “Dr. Strangelove” round table bickery thrown in, featuring flashbacks within flashbacks, and overlaps in time and space that require the viewer to often play catch-up, much like the unfairly maligned “Tenet” (“Ignorance is our ammunition.”)

Effect before cause is “Tenet’s” very coda (not a simple one). “Oppenheimer” looms over the same enigma. “They won’t fear it, until they understand it, and they won’t understand it, until they’ve used it.” This is the Oppenheimer quote most everyone knows and Nolan wisely realizes not even a three hour film can fully dive into its implications. As with “Tenet,” Nolan hones in on the idea that repeat viewings should only enrich the greatest of films. Via his parallax structure, he uses point-of-view film grammar as both a portent of doom and narrative withholding device. Certain scenes (unless one is already educated on the historical details) only fully come into focus once we see them from a second perspective, making “Oppenheimer” not unlike “The Prestige” as a cross-cutting balancing act of when to play the cards, versus patiently waiting for the opportune time to hide them up a sleeve.

It’s also a parallel film to “Dunkirk;” showing the Japanese side of World War II as opposed to the European; exploring how the war was won behind closed doors (and in the middle of nowhere), while thousands more physically risked and lost their lives on beaches and battlefields across the ocean. “Dunkirk” only referred to Nazis as “The Enemy,” and “Oppenheimer” makes a hauntingly similar statement about the unknowable. The former film is essentially isolated in one, open space, location, Dunkirk itself; “Oppenheimer” is a chamber piece that propels itself through time and space.

Once again circling back to paradoxes, Nolan’s film is grandiose despite its often opaque interiority and dialog driven narrative. It’s tremendous in scope yet intimate in perspective. There is a chasm of purposeful confusion between the two; Murphy’s performance a cipher of poetic self-catastophe. Right and reason combat each other like the heart and mind. We feel what Oppenheimer feels though we never come close to being capable of understanding how he thinks.

“Oppenheimer’s” marketing campaign almost reads as a countdown to the end of the world, one extremely reminiscent of the Swan Station from “Lost’s” Dharma Initiative, a clear fictional expansion of what started at Los Alamos. “That button has to be pushed” John Locke tells the audience, a self-proclaimed “Man of Faith” (named after a seminal philosopher) maintains. The Doctor, the “Man of Science” disagrees. Parallax and paradox. They might die if they don’t push the button and they have no idea what the hell happens every time they do.

“Inception” and “Interstellar,” are undeniably meta-statements on the consequences of living inside one’s imagination at the cost of family. “Tenet” and “Inception” are both easily read as allegories to the filmmaking process (Cobb and Neil both clear Nolan doppelgängers). “The Prestige” parallels two magicians with rival perspectives on how to approach the concept of showmanship. Do you push the button that will sell your artistic soul to sell tickets, or do you dedicate yourself so obsessively to authentic craft that you lose everything else in the process? “Oppenheimer” touches upon all of these questions. Sadly, its approach to family and its female characters only reinforces prior criticisms of Nolan’s screenwriting side. He does attempt to comment on the “sin,” in a key climactic scene, though, in the end, it’s not quite enough. However, part of the entire point is how perceived importance doesn’t excuse immoral action, perhaps even when the future of the world is at stake. “Man’s reach exceeds his imagination.”

It’s doubtful Nolan fully blames himself for the superhero crisis Hollywood is facing but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t an accidental prophet of the creative apocalypse. After all, he simply sees the effect before the cause. He made a film about Tesla, well before the world cared about Tesla, or had even heard the name Elon Musk (“See I’m not a monster. I’m just ahead of the curve.”) “Oppenheimer” can very much be read as a point of no return for the obsessive, visionary archetype, but it’s far more than that; a cautionary tale and character study as only this movie magician could make. As temporal physicist Daniel Faraday from “Lost,” would put it, “I don’t want to set off a nuclear bomb, Mr. Hume. I think I already did.”